I was facilitating the first meeting of a steering committee for a proposed province-wide public consultation on a painful and difficult topic involving abuse.

My colleague and I had worked hard to find a wide range of participants who all had a good deal of wisdom on how to deal with the topic and had a stake in the results of the conference. Most of these participants were service providers, not necessarily those who were personally affected, but who cared deeply about those where were. Survivors were reluctant to be identified publicly.

One woman who insisted on participating in the steering committee had a reputation for obstructing any meeting on the topic in nasty and very personal attacks, including staging very public walkouts that had scuttled any work on the topic.

I tried to make sure her views were heard, as well as everyone else’s ideas.

We had been working for two days and were getting very close to the time we had to finish so that participants could catch planes and other public transportation to get home. We were in the midst of a brainstorm to articulate the way the conference should address the issue, but I had been told that I could not use the consensus workshop method with cards, so I was using the flipchart method which presents challenges in showing common patterns among the ideas.

The process bogged down, and suddenly she stood up and declared, “I refuse to go on until you all admit I have the only right to an opinion.”

The group froze. At the front of the room, I noted in my head the words she had said. I noted the background information I knew about her.

Then I noted my reaction – a crouched defensive posture; and the reaction of the group – everyone looked down and tried to become invisible.

First I thought about why I had reacted in this way: I admitted to myself that her behaviour was threatening my right to lead the group, which also challenged my self-story of service. Then I thought about why this might have happened and realized that the group, afraid of attacks from her, had abdicated taking responsibility for her behaviour in the group, and left it to me to handle her for the whole meeting to this point.

So I thought about possible responses. Should I stand up to her and emphasize that everyone had a valid opinion? The consequences of that would likely be that she would then focus her attack on me personally, and I would not be able to facilitate the group. The whole group really needed to take responsibility for the situation. How might I get them to do that?

Intuitively, I pulled my chair over to the side of the table leaving the front of the room empty. I silently projected the question that the group needed to ask into the middle of the room. After a few minutes someone asked the question of her: “Why do you have the only right to an opinion on this topic?” She answered, “Because I am the only advocate in this room who speaks for the survivors”. She had a valid point hidden behind her behaviour. My co-facilitator and I had not been able to find survivors who would come out publicly to be on the steering committee to represent themselves.

Participants in the group began to speak up: “I know a couple of people that I can ask who will probably be willing to be a part of the steering committee…” Others volunteered to ask others that they knew.

Finally the group closed the meeting.

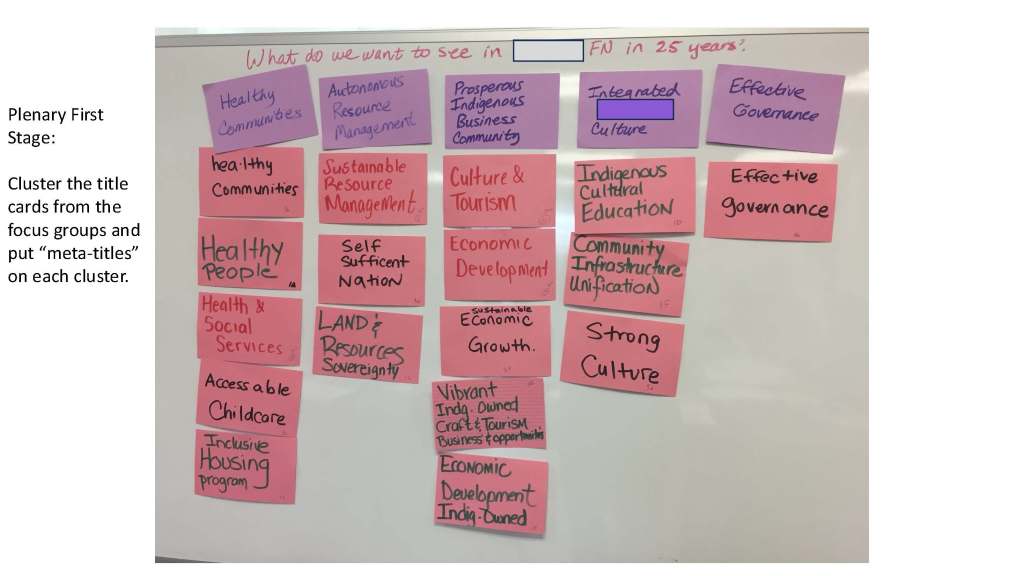

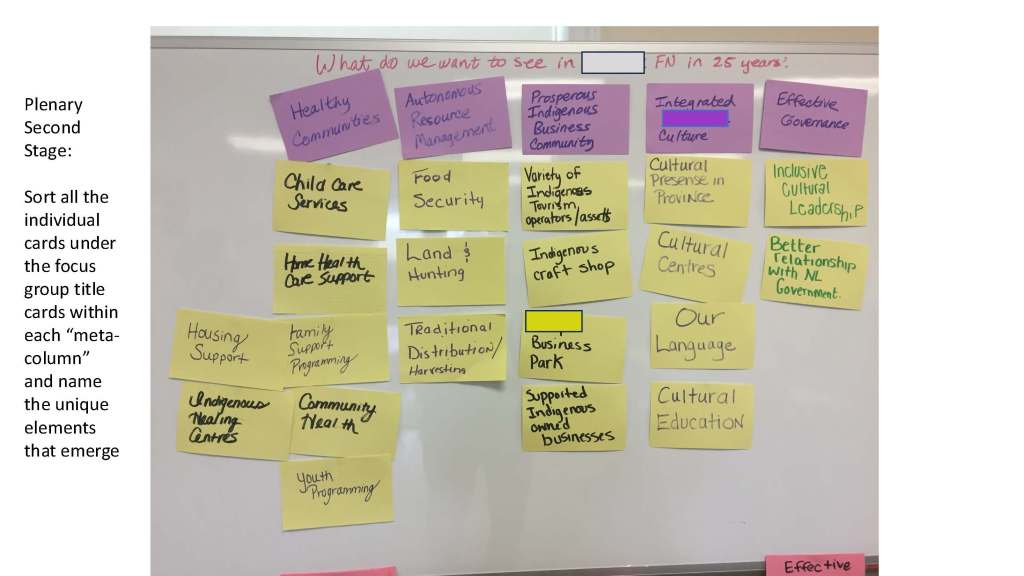

In the next meeting, survivors were present. Because the group had been unable to find the patterns in their brainstorm, my colleague and I had taken all the individual ideas from the first meeting, clustered them using our best understanding of their meaning by the people who had said them, and named the clusters. We shared the results with the whole group.

The woman who had caused the situation turned to her friend and said, “We don’t need to be here. They’ve heard us.” For the rest of the steering committee meetings she participated positively.

When the actual conference of a hundred people was held, her old behaviour re-occurred. She invented a reason and tried to stage a walkout. Survivors stood up and said “You don’t speak for us. We speak for ourselves, and we want to finish this consultation with results.”

The consultation was a success. Afterward I heard that people’s lives were changed positively because of their participation in the conference.

Note that my silent thinking process to address the issue in the steering committee followed ORID. It was not a focused conversation.

If you want to know more about the roots and history of ORID, contact the ICA in your country or http://ica-associates.ca ORID is also explained in depth in The Art of Focused Conversation, Second Edition, and Getting to the Bottom of ToP.